This paper below is a translation of a paper originally published in Korean. The translated content may differ from the actual content of the paper or the author’s intent. Therefore, if you wish to cite this paper, please refer to the original text of the publication.

Korean Journal of Gerontological Social Welfare vol. 76(3), pp.65-90

DOI : 10.21194/kjgsw.76.3.202109.65

KIM JUNGHYUN

Research Fellow, Research & Development, Seoul Welfare Foundation

HAN EUNHEE

Research Fellow, Korea Social Security Information Service

Abstract

The welfare blind spot discovery management system using administrative big data is being operated to respond welfare blind spots that do not received appropriate support even in a crisis situation. However, the current risk prediction model for vulnerable households has limitations in reflecting the needs among older adults. This study aims to explore the method of improving the risk prediction model for vulnerable households reflecting the needs of older adults. Focus Group Interviews(FGI) were conducted on 7 social work and policy experts in the field of older adults. The results from the analysis identified targets and predictor variables in older adult welfare blind spots which could be applied to the risk prediction model for vulnerable households. In older to prevent blind spots, the prediction model should consider the needs of older adults and regardless of whether they received or use welfare benefits and services. Applying predictor variables reflecting the needs of older adults and linking older systems to apply these variables can improve the accuracy of the predictive model and improve limitations of application-based service provision. Subsequent researches should focus on the function and performance evaluation of the welfare blind spot prediction system that reflects the needs among older adults.

I. Introduction

The Basic Livelihood Security Act of Korea (Act No. 16734, amended on December 3, 2019) was enacted in 1999 to guarantee a certain level of living to all Korean nationals. How well has the social security system, which has been steadily expanded over the past 20 years, guaranteed the basic living standards of the people? The term “blind spot” (死角地帶) is defined in the Standard Korean Dictionary as an area that is not reached by attention or influence. In this context, people who are unable to receive the necessary benefits or services from the government, which has the obligation to guarantee them, even though they are struggling to live, are said to be in the “blind spot of welfare” (Kim Eun-ha et al., 2015). As of April 15, 2021, there are over 620,000 news articles about “welfare blind spots” on Google, and only 250 or so articles have been found in the first four months of 2021. Most of these articles deal with cases of welfare blind spots or prevention and response to them. Among the many cases covered in the articles, the most representative case related to the welfare blind spot is the “Songpa Three Sisters Incident,” which occurred in February 2014. While the Songpa Three Sisters Incident is a representative case that has raised social awareness of the welfare blind spot, the “Banpo Mother and Daughter Incident” that occurred in December 2020 shows a glimpse of the continuing tragedy in our society, despite various attempts to address the welfare blind spot, such as the amended Basic Livelihood Security Act or emergency welfare support following the Songpa Three Sisters Incident (Dong-a Ilbo, 2020).

To prevent the tragedies caused by the welfare blind spot, it is necessary to identify and provide appropriate benefits at the right time for the needs and problem situations of socially excluded groups. The Social Security Information System is an electronic management system that integrates, links, processes, and records information on social security activities implemented by central administrative agencies and local governments (Article 37 of the Social Security Basic Act [Enacted on July 8, 2020] [Law No. 17202, April 7, 2020, partially amended]). If the information accumulated in the Social Security Information System is processed efficiently, the welfare blind spot can be identified on a daily basis (Kim Eun-ha et al., 2015). Accordingly, the government has been operating the “Welfare Blind Spot Discovery Management System” based on administrative big data since 2015 to further improve the daily discovery of welfare blind spots (Ministry of the Interior and Safety, Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2021). However, the current welfare blind spot discovery management system, which mainly uses economic crisis information, has limitations in identifying the elderly welfare blind spot, which occurs for complex reasons.

South Korea is expected to enter a super-aged society in just four years, in 2025 (Statistics Korea, 2020). As of 2020, 22.8% of households are headed by someone aged 65 or older, and it is projected that by 2047, 49.6% of all households will have at least one member aged 65 or older (Statistics Korea, 2020). Even without considering the population size, it is important to identify the elderly who are in the welfare blind spot. In old age, people face functional decline due to aging and role loss at the same time, and they lack the necessary physical, psychological, and social resources to cope with these challenges (Kim, 2020). As people age, their dependence on others increases due to decreased physical function, memory loss, and muscle mass loss. They also have more contact with healthcare providers and caregivers, but less social contact with neighbors and friends (Key & Culliney, 2018). Despite the ongoing efforts to reduce poverty through public transfers, the relative poverty rate of people aged 66 or older in South Korea is the highest among OECD member countries (Kim et al., 2020; Statistics Korea, 2020). Moreover, the needs of the elderly in the welfare blind spot are directly linked to their survival (Kwon et al., 2012). Therefore, it is necessary to prevent the elderly from falling into the welfare blind spot and to respond to this issue socially.

Therefore, this study aims to explore the direction of identifying elderly welfare blind spots by utilizing the welfare blind spot discovery management system, focusing on the crisis characteristics of the elderly and elderly households. To achieve the research objective, this study conducted focus group interviews (FGIs) with practitioners in the field of elderly welfare and policy experts. This study differs from previous studies in that it focuses on the potential and improvement plans of the welfare blind spot discovery management system as a response measure for elderly welfare blind spots.

II. Literature Review

1. Previous Studies on Elderly Welfare Blind Spots

Welfare blind spots can be defined in a variety of ways depending on the purpose, target, form, and scope of benefits provided. According to Kim Eun-ha et al. (2015), domestic studies on welfare blind spots have mainly focused on the basic livelihood security system. The similar term “non-recipient poor” also focuses on the public assistance blind spot (Han Kyung-hoon, Kim Yoon-min, and Heo Seon, 2019), and refers to those whose income recognition amount does not reach the poverty line of 40% of the median income, but do not receive public assistance benefits (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2019). However, the public assistance system is just one example when discussing the concept and scope of welfare blind spots. Depending on whether the people exposed to social risks are workers, local contributors to the National Pension, or applicants for long-term care grades, blind spots can be applied to a variety of areas, including social insurance, social services (Kim Chan-woo, 2014; Jeong In-young, 2015; Bang Ha-nam and Nam Jae-wook, 2016). The concept of welfare blind spots also varies depending on how comprehensively a particular system or program targets or how much benefits it provides (No Hye-jin, 2016).

In this context, the concept and scope of elderly welfare blind spots are operationalized depending on the purpose and method of the research. Previous studies that focused on public assistance found that the elderly are vulnerable to poverty due to income decline and need the protection of the basic livelihood security system (Lee Seung-ho, Koo In-hoe, 2010; Kim Hee-yeon, 2013; Kim Seung-yeon et al., 2019; Han Kyung-hoon, Kim Yoon-min, and Heo Seon, 2019). However, among the vulnerable population, the elderly are also relatively well-off in terms of income security programs compared to other age groups (Kang Shin-wook, 2017). Studies on elderly welfare blind spots other than public assistance focused on aging care. Kim Tae-il and Choi Hye-jin (2019) proposed voluntary long-term care benefit application and sufficient private care as criteria for the blind spot, and analyzed that the coverage of long-term care services and the effectiveness of the system in Korea are lower than those of OECD countries. Kim Yoon-young and Yoon Hye-young (2018) suggested the application direction of the care blind spot in Korea by borrowing overseas cases of community care. Jung Kyung-hee and Min So-young (2017) examined intervention strategies for building a care system in the community based on the experience of a specific project conducted for the elderly living alone. The characteristics of the elderly in the welfare blind spot that previous studies have focused on are the household type, that is, the elderly with weak social support networks (No Jae-cheol, Go Jun-gi, 2013; Jung Kyung-hee, Min So-young, 2017). As the elderly population has increased, discussions have continued on the care blind spot that is directly linked to the daily lives of the elderly, in addition to public assistance. However, research on the diverse characteristics, influencing factors, and solutions for the elderly in the blind spot is still insufficient.

2. Elderly welfare services to be considered in blind spots of elderly welfare

To define the scope of elderly people who are in the welfare blind spot, it is necessary to understand the types and eligibility criteria of the elderly welfare programs operated by the government. According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare (2020), elderly welfare programs are divided into four major categories: health insurance, income security, housing security, and social services (see <Table 1> ). Programs for elderly care include the long-term care insurance system, the improvement of functions of elderly housing, medical, home, and welfare facilities, and dementia and health care programs such as dementia centers, public guardianship for dementia, and dementia and health screenings. Support for social activities and leisure activities includes support for the operation of community centers and senior citizen centers. Elderly care and support services include customized care for the elderly (hereinafter referred to as “matching service”), shared living homes for the elderly, operation of the elder abuse prevention center, education on prevention of elder abuse and human rights, free meal support, and discovery or protection of waste collectors (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2020).

| Business name | Qualification criteria | Note | |

| Health guarantee | Elderly long-term care insurance | Those aged 65 or older or those under 65 suffering from geriatric diseases with moderate or higher severity (grades 1 to 5) who require nursing care. | ’08.7.1. enforcement |

| Senior welfare facility (medical) | A person who requires medical care due to a geriatric disease, etc. ⋅ A beneficiary pursuant to Article 15 of the Elderly Long-Term Care Insurance Act ⋅ A basic beneficiary (living allowance, medical allowance) | Local transfer project | |

| Welfare services for the elderly at home (visiting nursing care, daytime/short-term care, visiting bathing service) | ⋅Long-term care benefit recipients ⋅Persons aged 65 or older who are mentally or physically weak or disabled ※If the user pays the full cost of service use, the user must be 60 years of age or older. | Local transfer project | |

| Dementia relief center operation | Dementia patients and their families | ||

| Dementia screening project | Person over 60 years of age ⋅ Diagnosis/differentiation test is for those with income below 120% of the standard median income. | ||

| Dementia treatment management support project | Dementia patients over 60 years of age ⋅Those with a standard median income of 120% or less | ||

| Guaranteed income | Senior job and social activity support project | Seniors who can participate in senior job and social activity support projects ⋅Public interest activities are for basic pension recipients ※ Depending on the business content, people over 60 years of age can also participate in some projects. | |

| Housing Guarantee | Senior welfare facility (residential) | As a person who has no problems with daily life ⋅Basic recipients (living allowance, medical allowance) and those who do not receive adequate support ⋅Urban workers, elderly people from households with monthly average income below ※If the user pays the full admission cost, 60 years of age or older | Local transfer project |

| Provision of social services | Customized care service for the elderly | Those who are 65 years of age or older, recipients of the National Basic Living Security, second-lowest class, or basic pension recipients who do not qualify for similar overlapping projects ※Similar overlapping projects: long-term care insurance for the elderly, housework/nursing visit support project, veterans home welfare service, activity support project for the disabled | Starting in 2020, senior care projects (6 types including comprehensive care and care services) will be integrated. |

| Senior leisure welfare facilities | ⋅Senior Center: 65 years or older ⋅Senior welfare center: 60 years or older | Local transfer project | |

| Free meal support for seniors who are concerned about not eating well | Seniors over 60 years old who are concerned about skipping meals | Local transfer project | |

| Senior citizen preference system | For those aged 65 or older⋅Railways, subways, national/public parks, etc. | ||

<Tabel 1> Eligibility criteria for major senior welfare projects in 2020

Source: Ministry of Health and Welfare (2020)

When considering the characteristics of old age, discussions on elderly welfare blind spots should not only cover income security, but also focus on care-related areas. This is because in old age, functional decline occurs due to aging, and it is essential for others to care for them as they are limited in leading an independent life (Jeon Yong-ho, 2020). In the major elderly welfare programs of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (2020), all areas except income security and housing are directly related to care. The long-term care insurance system for the elderly, which was implemented in 2008, is the most representative elderly care system in Korea (Lim Jeong-gi, 2019). Based on the application for long-term care recognition, a long-term care recipient is selected and home-based care or facility care is provided through long-term care institutions (National Health Insurance, 2020). As of the end of 2019, there were a total of 1.11 million long-term care insurance applicants, and 772,000 (recognition rate of 83.1%) were approved. The recognition rate of long-term care insurance for the elderly population in Korea is about 9.6% (National Health Insurance, 2020). The elderly care service for the elderly living in the community was integrated into the customized care for the elderly (hereinafter referred to as “matching”) service in 2020. This is because there is a blind spot in elderly care. Until 2019, elderly care services were operated in six fragmented forms (basic care, comprehensive care, social relations activation for the elderly living alone, self-reliance support for the early elderly living alone, short-term household service, and linking local community resources). As various organizations provided elderly care services, similar overlapping cases occurred, and cases of the elderly who had a need for care but did not receive any support also occurred simultaneously (Jeon Yong-ho, 2020).

The institutional causes of cases of elderly people not receiving any support despite their needs are largely divided into structural limitations and limitations of applicationism. As shown in < Table 1>, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s welfare programs for the elderly select recipients based on different criteria. Qualification criteria become more diverse when including elderly welfare projects carried out by local governments or local governments. If the eligibility criteria are met, a single senior can receive multiple benefits or services regardless of who provides them. However, the more diverse and complex the qualification requirements are, the more likely they are to be eliminated during the verification and granting process due to using similar or overlapping services, or those who do not meet specific criteria may be excluded (Editorial Department, 2019; Heo Yong-chang et al., 2020). Blind spots in elderly welfare may occur depending on the structural limitations of the system. In addition, if the senior citizen meets the eligibility requirements but stops applying for benefits or services due to ignorance or difficulties encountered during the application process, the elderly person is placed in a welfare blind spot (Editorial Department, 2019; Heo Yong-chang et al., 2020).

3. Current status and limitations of the welfare blind spot identification and management system

In order to prevent blind spots in welfare that arise due to structural or application-based limitations, the “Act on the Use and Provision of Social Security Benefits and Identification of Beneficiaries” (hereinafter referred to as the Social Security Benefits Act, Law No. 17689) was enacted in December 2014. Among the relevant laws, it is necessary to pay attention to the provisions regarding the obligation to identify people who are judged to be in a crisis situation as a result of information processing and the obligation to provide appropriate social security benefits to households in crisis. Based on these regulations, the government used the Social Security Information System in 2015 to link and analyze information from 23 types of 13 institutions and began to identify at-risk households on a pilot basis. Since then, the scope of information on vulnerable groups needed to discover blind spots has gradually expanded, and as of January 2021, 34 types of information obtained from 18 organizations are being used (see <Table 2>).

| Division | Link information |

| Non-payment of bills | Power outage, water outage, short gas, electricity bill arrears, health insurance arrears, management fee arrears, public lease arrears, communication fee arrears |

| Standard of living measurement | Long-term care for elderly people with dependent obligations, excessive medical expenses, households vulnerable to renting, households vulnerable to monthly rent, financial delinquency |

| Change in situation | Persons discharged from facilities, failure to apply for basic emergency, business closure, fire damage, disaster damage, death of household head |

| Labor crisis | Unemployment benefit receipt, non-receipt of unemployment benefit, unemployment after industrial accident care, unemployed day worker, individual extended benefit eligibility |

| Related to other welfare projects | Students at risk, no nutrition plus support, visiting health care group, diaper formula support, newborn hearing loss confirmed |

| Etc. | High risk of suicide, crime damage, health insurance payment |

Source: Ministry of Public Administration and Security⋅Ministry of Health and Welfare (2021, reorganized p.81)

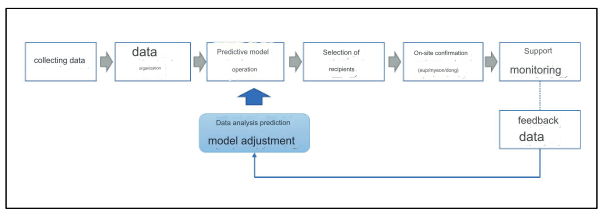

The Social Welfare Blind Spot Discovery and Management System has been in continuous operation since 2016 (Kim, E. H., et al., 2016; Choi, H. S., et al., 2018a; Choi, H. S., et al., 2018b). The process of discovering social welfare blind spots through the Social Welfare Blind Spot Discovery System is as follows. First, data is collected and linked from each affiliated institution every two months, and then the data is refined to create a personal data set that can be used for analysis (Lee, W. S., et al., 2020). The analysis target is applied to the social welfare blind spot prediction model to calculate the risk of each individual falling into a blind spot. The Ministry of Health and Welfare then determines the scale of discovery for each round of two months, from about 50,000 to 200,000 people, and extracts “high-risk households” based on the risk of crisis calculated through the prediction model. The information of these individuals is distributed to local governments, and public officials from the visiting public health team in the eumyeondong district confirm the information of the target and conduct a home visit survey. The results of the measures taken at the eumyeondong district level for the discovered targets are summarized as statistics on the day after they are entered into the Social Welfare Blind Spot Discovery and Management System, and the content of the benefits or services received by the final discovered targets is used as feedback data for model improvement after monitoring. (See Figure 1.)

Source: Lee Woo-sik et al. (2020, p.64-p.65 reconstructed)

The welfare blind spot discovery management system calculates the probability that the acquired subjects will be in welfare blind spots through machine learning-based Predictive Risk Modeling (PRM) (Hyun-soo Choi et al., 2018a; Hyun-soo Choi et al., 2018b; Lee Woo-sik et al., 2020). Machine learning, a field of artificial intelligence (AI), is an algorithm in which computers learn on their own from accumulated data. Using a machine learning-based prediction model to discover welfare blind spots is more efficient than using a comprehensive survey or traditional analysis tools (Eunha Kim et al., 2016). However, it may be predicted as not being a welfare blind spot when in fact it is (False Positive, Type 1 error), or it may be predicted as a blind spot even though it is not a welfare blind spot (False Negative, Type 2 error). Additionally, if the predictors (independent variables) and prediction targets (dependent variables) of the risk prediction model are not clear, it is difficult to secure reliability and validity (Murphy, 2012; Gillingham, 2016 recited). As seen above, the current welfare blind spot detection and management system is designed so that the machine learns by feeding back information on whether subjects predicted to be high-risk crisis households and distributed to towns, villages, and dongs actually received welfare benefits or services. In other words, regardless of actual welfare needs, only those who are determined to be crisis households (households of people judged by the head of a security agency to be in a crisis situation) and receive welfare benefits under the Social Security Benefits Act are defined as welfare blind spots. As a result, the prediction model of the welfare blind spot discovery management system excludes from discovery targets individuals or households who do not receive benefits or services due to structural blind spots and limitations in applicationism, or who are already receiving one or more benefits.

In addition, the variables used to predict the risk of blind spots in the current welfare blind spot detection and management system include material hardships such as power outages, water outages, and gas due to non-payment, changes in circumstances, work crises, and housing crises. (Refer to <Table 2>). Currently, in order to reflect household characteristics according to the number of household members, it is divided into a single-person household model and a multi-person household model (Choi Hyun-soo et al., 2018b; Lee Woo-sik et al., 2020). However, household characteristics according to age and life cycle are not considered in predicting welfare blind spots. Even if they have the same crisis variables, very old people with no ability to work and weak physical functions may be in a more dangerous situation than young people or older people. At the same time, it is highly likely that the elderly are already eligible for welfare benefits such as basic pension. As mentioned earlier, in the current welfare blind spot discovery and management system, those eligible for public benefits are already excluded from discovery. In other words, elderly people in receipt of benefits/services whose welfare needs are not actually met or who are in a crisis situation are excluded from discovery. In order to reduce such errors, it is necessary to define blind spots in elderly welfare by considering the special characteristics of the elderly and develop a prediction model specialized for elderly welfare that reflects information that can predict this.

III. Research method

In order to explore the characteristics of blind spots in elderly welfare and ways to discover them, this study conducted two focus group interviews (FGI) with field experts and policy experts in elderly welfare practice. FGI has the advantage of being able to obtain the information needed for research more efficiently during a limited period of time than individual interviews (Bryman, 2004). In order to smoothly collect data, the researchers presented FGI participants with pre-planned discussion topics in a semi-structured manner and then allowed them to talk about them freely. When FGI is conducted on how elderly welfare experts understand and feel blind spots, in the process of exchanging ideas with each other, the meaning of elderly welfare blind spots is identified, that is, the ‘predicted target’ of the elderly welfare blind spot risk prediction model and the blind spot. Specific information on ‘predictive variables’ applicable to identifying elderly people can be collected (Jae-eun Seok, Hye-jin Noh, Jeong-gi Lim, 2015; Jeong-hyeon Kim, Yong-ho Jeong, and Hye-ja Jang, 2020).

This study adopted a purposive sampling method to recruit people with sufficient experience in the field related to blind spots in elderly welfare and who can present meaningful opinions as FGI participants. The recruitment criteria for participants in the first FGI, which was conducted targeting senior welfare practice sites and policy experts, are ① having at least 10 years of experience in major senior welfare policy and implementation sites, and ② currently serving as the head of a related institution or organization. In addition to the first FGI, which derived the characteristics and cases of elderly people in the community who are at risk of being in blind spots, 2 surveys were conducted targeting experts in the long-term care system, Korea’s representative care system, to understand the reality of care blind spots in more depth. Primary FGI was performed. The recruitment criteria for participants in the 2nd FGI are ① more than 5 years of experience in senior welfare policy research and ② a doctoral degree holder currently in charge of research on the long-term care system. The first expert FGI was held for 3 hours on August 4, 2020, focusing on the meaning of blind spots in elderly welfare, the characteristics of elderly households at risk of being in blind spots, and the government’s role in discovering blind spots. The 2nd FGI was held for 2 hours on October 23, 2020, and in addition to the matters discussed in the 1st FGI, it focused on elderly care policy planning and delivery system structure, and additional information that can be linked to the welfare blind spot identification and management system. It has been done.

| Division | Participants | Gender | Age range | Career | Field |

| 1st FGI | Field expert 1 | M | 40s | 15+ years | Long-term care facility operation |

| Field expert 2 | F | 40s | 20+ years | Operating a comprehensive senior welfare center | |

| Field expert 3 | F | 50s | 15+ years | Operating a support center for the elderly under the Ministry of Health and Welfare | |

| policy expert 1 | M | 50s | 15+ years | Research on jobs and social activities for the elderly | |

| Secondary FGI | Policy expert 2 | F | 40s | 7 years or more | Welfare delivery system and long-term care system |

| Policy expert 3 | F | 40s | 5 years or more | Elderly welfare and long-term care system | |

| Policy expert 4 | F | 50s | 10+ years | Statistics related to long-term care system |

Before conducting the FGI, the researchers informed the participants that they could withdraw their comments at any time of their choice and that there would be no disadvantage. The FGI proceedings were recorded with the consent of the participants, and the recordings were organized into transcripts and thematic analysis methodology was applied. The researcher read the transcripts repeatedly, open-coded new content regarding blind spots in elderly welfare, and then reviewed the relationships between the derived codes. Afterwards, we checked the transcripts to make sure there were no missing details to understand the content related to uncovering blind spots in elderly welfare using the social security information system.

IV. Results

The results of analyzing the data obtained in this study and categorizing them by topic are shown in <Table 4>. As a result of analyzing the FGI data, two areas were derived: prediction targets and predictors of blind spots in elderly welfare, and each area consisted of various upper and lower categories. The categories organized as prediction targets for blind spots in elderly welfare can serve as a basis for expanding the prediction targets of the blind spot risk prediction model. The characteristics and linkage information of elderly people in blind spots present information that can be newly linked to the risk prediction model in addition to the current linkage information presented in <Table 2>.

| Area | Parent Category | subcategory |

| Prediction targets for blind spots in elderly welfare | Definition of blind spots in elderly welfare | Narrowly defined |

| Major senior welfare policy projects to set prediction target range | Customized care service for the elderly | |

| Policy projects requiring additional review | Alcoholism case management project, elderly protection agency | |

| Predictors of blind spots in elderly welfare | General characteristics of elderly people in welfare blind spots | Household type, mismatch between administrative address and actual residence, social network, low information accessibility |

| Systems that require information linkage | Elderly customized care system, vulnerable elderly support system, elderly job work system, long-term care integrated information system |

- Prediction target for blind spots in elderly welfare

1) Definition of blind spots in elderly welfare

FGI participants agreed that even if elderly households are currently receiving benefits or services within the system, they should be considered to be in a blind spot if their needs are not fully met. This is because the traditional definition of the elderly in a blind spot, which is based on whether they receive social security and social service benefits, is too narrow. In this context, FGI participants agreed that it is necessary to expand the target of predicting the blind spot of elderly welfare to “elderly in a state where needs are not fully met.” This would mean that even elderly people who are currently receiving benefits or services within the system could be considered to be in a blind spot if their needs are not being met.

If there is a system, it seems that blind spots are mainly problems that are not within the system. We are approaching it by defining it in a very narrow scope, but I think we need to think about whether this approach is right… (omitted)… When problems like lonely deaths arise, there are many people who are beneficiaries or in the institutional system. He is a recipient, so why is he even in the picture? Instead of being conscious of the problem, we need to approach whether the institutional system is really sufficient based on a more universal standard, but because we focus too much on the crisis and the results. (omitted)… Even if it is satisfying the need, it is not enough or the connection is poor. If you say anything, it’s over. I believe that the definition of this system lies in the highest agreement. The extent to which the public assistance system operates within the scope of recipients and non-recipients. That’s not enough. You can only go into it thoroughly if you approach it with a definition of blind spots that is much more universal than that. (Policy Expert 1)

2) Major senior welfare policy projects to set the forecast target range

The key policy projects that should be considered in order to set the scope of blind spots in elderly welfare are the major elderly welfare projects presented in <Table 1>. In particular, a project that needs attention in the blind spot of elderly care is customized services. This content was revealed through cases of elderly people whose needs were not met when FGI participants shared their experiences about blind spots in elderly welfare. Although the matching service was introduced in 2020 to overcome the blind spot in elderly care due to the limitations of existing elderly care services, FGI participants are still concerned about the possibility of blind spots occurring because elderly people who may use similar services are excluded from customized services. did. If you stop using care services and receive a long-term care rating, you may not receive the care service benefits you were previously receiving even if you do not receive long-term care services.

I don’t view the part of receiving any service as a blind spot. However, even if these people are receiving care services, there are vulnerabilities in those services. (Field expert 3)

3) Policy projects requiring additional review

In addition to the major senior welfare policy projects mentioned earlier, additional central government projects that can be considered include alcoholism case management projects and senior citizen protection agencies. As a result of FGI, it was confirmed that there is a need for welfare related to the project, but there is a high possibility of being in the blind spot of the project due to ignorance or difficulty in accessing it. There is a need to further examine the relevant projects from the perspective of expanding the scope of prediction targets for blind spots in elderly welfare.

First, the main service target of the alcoholism case management project is the homeless, but the elderly, who are the majority of the alcoholics case management project, are elderly households at risk of being in the blind spot. In addition, although the number of elderly victims of abuse is also increasing as the elderly population increases, elderly households that receive services such as temporary protection, legal support, and professional counseling from institutions specializing in elderly protection are only a portion of the elderly who receive social security or care blind spots. (Jongnyeo Seo, Sunyoung Park, 2020).

The problem with older people these days is that many of them are alcoholics, and there are surprisingly many elderly criminals… (omitted)… I’m honestly worried about these people, too. (Field expert 3)

I think things like mental disorders and alcoholism should be looked at even if it is a general policy rather than a senior citizen welfare policy. Because it’s a blind spot. (Policy Expert 2)

Cases such as abuse and violence are often reported by vulnerable groups. So, I think it could be a key even if it is not a senior citizen care policy. (Policy Expert 3)

2. Predictors of blind spots in elderly welfare

1) General characteristics of elderly people in welfare blind spots

FGI participants are elderly, elderly people living alone, households consisting of only elderly people, and households with children are highly likely to fall into the blind spot of elderly welfare. In particular, attention is paid to elderly people who have just started living alone and elderly parents who have disabled children to support. It was emphasized that it must be done. In addition, if a female elderly person in a household in which one member of the household has received long-term care is the main caregiver, the burden of care increases and the possibility of facing an economic or emotional crisis is greater than in other cases.

For example, if a spouse dies, the elderly person becomes a single person involuntarily. In the case of a death, it is called an early single elderly person within five years. This means that the elderly person has experienced a significant loss and may be struggling to cope with their grief. They may also be at risk of depression or other mental health problems. (Field Expert 3)

It is important to check for people with chronic diseases who need long-term care, but who are living in elderly couples or single households. These people may not be able to access the care they need because they are not considered to be “vulnerable” by the government. (Policy Expert 3)

Elderly people who are supporting disabled children can also be at risk of falling into a blind spot. These people may be providing a great deal of care to their children, which can take a toll on their own physical and emotional health. They may also be at risk of financial hardship. (Field Expert 2)

The government is conducting a survey of the status of caregiving burden and providing family counseling to at-risk households. This is a good start, but it is important to also consider a gender perspective. For example, if a husband is sick, his wife may be the primary caregiver. However, she may not be able to access the same level of support as a husband who is caring for a sick wife. (Policy Expert 4)

Elderly people whose registered residence and actual residence are different due to personal or family relations are not able to be identified through administrative systems and are likely to fall into the blind spot of elderly welfare. In this regard, Field Expert 2 shared a case in which a basic living allowance recipient with a mental illness who had no fixed residence disappeared and could not be contacted, and the safety and life of the elderly had to be confirmed through cooperation between the senior welfare center, neighborhood community center, district office, and neighbors.

People in the welfare blind spot have their administrative address in Yongsan-gu, but they actually live in Gwanak-gu. They are always excluded from administrative measures. They are included in the welfare blind spot even in the elderly tailored care service. In the case of COVID-19, the homeless were excluded, which caused problems. (Field Expert 3)

When we did the basic project last year, the subjects had to be connected from Happyeeum in the eup-myeon-dong to judge the eligibility. So, it has to be within the administrative region. (Policy Expert 4)

People who are homeless due to mental problems need to have an address to receive living expenses. Such people, even if they go out, where they are, and we once stopped it. We had to figure out the destination, but we had to negotiate with the district and the dong for the benefits. They appeared to request it. I had also confirmed their life or death. Histrionic mood disorder. I was so curious because I couldn’t see you. They had just put their name on the residence for a little rent. I raised an issue that the benefits were not justified, but it is the right person to receive it. Because it is a habit of being homeless or such. It is difficult because individual consent is required for hospitalization treatment. (Field Expert 2)

Elderly people or households with elderly people who lack social support may find themselves in a blind spot if they do not know that they are the target of the policy due to limitations in applying, or if they do not know how to apply even if they know. Field experts responded that word of mouth from neighbors is almost the only way to discover reclusive elderly people who are highly depressed and have a high risk of suicide. They also agreed with the opinion that active elderly people who do things such as picking up waste paper, even if they equally need financial help, have a lower risk of being in a blind spot than secluded elderly people. As non-face-to-face services expand after COVID-19, elderly people who do not have cell phones or cannot understand information such as text messages but have difficulty obtaining information may be more likely to fall into blind spots.

In the case of single elderly people, information support is also included. There are many people who are seriously isolated from information. We saw this as one of the social supports, as it could be a support network for receiving welfare information. (Field Expert 3)

There are also quite a few cases where people do not receive it because they do not know. Even if the state provides a lot of information, the elderly are classified as an information-isolated group, so it is difficult to actually recognize the information. We need to find the people who are hiding. The reclusive elderly people that I mentioned earlier were surprisingly deeply involved in depression or loneliness when they took a class to make friends with single elderly people, but even the local residents did not know. It is word of mouth. If even one or two elderly people know. These are the real welfare blind spots. They have no will, they are at high risk of depression or suicide. There are cases where welfare blind spots do not receive information because they do not know, but there are also cases where they are neglected. These people are large. However, in the field, we do not see elderly people who collect waste as a blind spot. The blind spot is high-risk for people who do not do any activities at all. (Field Expert 2, 3)

Of the 475 elderly people who are the target of care, only about 100 have smartphones. Even if a text message comes in that can receive information, many people do not see it well. There are also many people who have low understanding or cognition. What does a confirmed case mean? What does negative or positive mean? When I asked if you could watch an online video, you said you didn’t know. I thought it was natural that you could do it. Even if you pour in a lot of information, you are isolated from information, so the best thing is word of mouth by peers. The promotion that is done by word of mouth is that the person next to me is also depressed. I told you that, so I went to find it and did it. (Field Expert 2)

2) Systems that need to be linked with the Welfare Blind Spot Discovery and Management System

According to the FGI results, the information networks that need to be linked with the Welfare Blind Spot Discovery System to increase the possibility of discovering the elderly welfare blind spot are the Elderly Tailored Care System, the Vulnerable Elderly Support System, the Social Welfare Facilities Information System, the Elderly Employment Work System, and the Long-Term Care Information System. Although the systems that need to be linked with the Welfare Blind Spot Discovery System are diverse, it is necessary to link information on service application dropout and suspension and the reasons for them. The following information needs to be linked by system to identify elderly people in the elderly welfare blind spot.

First, it is necessary to link information on elderly households that have experienced fire or gas accidents within a certain period of time through the Vulnerable Elderly Support System, an information system operated by the National Social Welfare Information Center, or elderly households that have applied for care services but have not been linked to services. It is also necessary to link information on households with elderly people who have entered or discharged from living facilities within a certain period of time in the integrated history information of the Social Welfare Information System, and elderly people who have reached the age of 65 with disabilities.

During holidays or holidays, there is a risk of accidents due to dementia. They oppose being sent to a living facility because they will lose their benefits. (Field Expert 1)

The gap between the use of long-term care services for people with disabilities and those who are 65 years of age is too large. There are many problems because the services are not designed to meet the needs of people with disabilities. There can be problems if the person in charge is not clear whether they are a senior or a person with a disability. (Policy Expert 4)

The elderly who participate in public activities, which are the largest scale of the elderly employment and social activities support program, are likely to experience financial difficulties during the period from December to February each year due to the structural limitations of the program. These structural limitations include the fact that the program is only offered for a limited period of time each year, and that the number of participants is limited. Elderly who applied for public activities participation in the elderly employment and social activities support program but were excluded despite being recipients of basic living allowances, or those who discontinued halfway, are also at risk of being in a blind spot. This is because they may not have other sources of income to support themselves during the time when the program is not offered. Therefore, it is necessary to link the information of elderly who want to participate in the elderly employment program but were excluded and those who are waiting in the elderly employment business system managed by the Korea Institute for Human Resources Development. This will help to ensure that these elderly are able to find other opportunities to participate in the program, or to receive other forms of assistance. Additionally, elderly who participated in the program but discontinued public activities participation due to health problems or old age are at high risk of being in the elderly welfare blind spot if they do not receive appropriate wages and services. Therefore, it is important to ensure that these elderly are able to access appropriate support services, such as disability benefits or long-term care services.

The elderly employment program is only for 9 or 10 months, and the remaining 2 months are without pay. This is a limitation of central policy. The overall structure is unstable. (Policy Expert 1)

In the elderly employment program, there are people who have a zero activity capacity. Is it reasonable for someone who needs help to work? Many people also drop out halfway. … Many people are also excluded from the job due to the supporting obligation criteria. It would be good to see the dropouts. (Policy Expert 1)

In the elderly employment program, only 10 to 20% of people are discontinued due to health problems. If you do it for about 3 years. As you get older, you may become more vulnerable. … For those who have met the criteria for income and other things, it seems necessary to provide continuous management and linkages if they are excluded due to a difference of 5 points in the scoring system. (Field Expert 2)

It is necessary to link information from the long-term care information system, including long-term care grade, benefits being used, whether a short-term long-term care grade upgrade application has been made, whether the household has received family counseling support, and the gender of the main caregiver in households consisting of only the elderly. According to the results of the FGI, the elderly who are particularly at risk of being in the elderly welfare blind spot are those who do not have their desire to upgrade their long-term care grade fulfilled, and those who have not used health care or care services after being diagnosed with long-term care grade. This is because they may be in the blind spot of elderly care even if they have a desire to use more care services, but they do not receive an upgrade rating.

The elderly who are not using long-term care benefits are the ones who can be covered by the system. On the contrary, there is a much higher possibility of problems arising in the situation where they are receiving care through long-term care benefits. (Policy Expert 4)

Even while receiving long-term care, there are people who want to adjust their long-term care grade. The faster the upgrade speed is, the more likely it is that it will not lead to a high upgrade adjustment. In any case, it is a change from latent needs to expressed needs. Some elderly who are receiving long-term care may find that the care they are receiving is not enough to meet their needs. These elderly may want to adjust their long-term care grade in order to receive more care. However, the faster the upgrade speed is, the more likely it is that the elderly will not receive the high upgrade adjustment they need. (Policy Expert 3)

The family counseling support project, which is part of the elderly long-term care system, was introduced in 2015 to provide 10 sessions of professional counseling (individual counseling, group activities, etc.) to reduce the stress of family caregivers who have a high sense of caregiving burden among the families of long-term care recipients. The service was provided to about 2,200 family caregivers in 2020, and the final target was selected through a caregiver burden survey. The average age of the target of the family counseling support service in 2019 was 69 years old, and it was confirmed that the burden of care in households where the elderly care for the elderly (‘nono care’) is large.

The government is conducting a caregiver burden survey and institutionalizing family counseling for vulnerable households. The main target group is those with high caregiver burden and high depression. Within this group, we analyzed that the elderly who care for the elderly (‘nono care’) are at a higher risk. (Field Expert 3)

Chronic patients are more likely to be in the care blind spot. The information on whether someone is a chronic patient can be obtained from the National Health Insurance System by using information on the users of various types of drugs. In addition, those who have received long-term care grades or have never used medical services even though they are elderly are also likely to have been neglected in the care blind spot. Based on the ‘Outpatient/Inpatient Medical Information’ of the National Health Insurance System, it will be possible to link the information of long-term care recipients or the elderly who have never received medical treatment for more than 1 to 3 years even though they are elderly.

If we use the National Health Insurance data on multiple drug users, we can identify all chronic diseases. It seems that people who take multiple drugs are prioritized over those who take them for a long time. This means that most chronic patients will be identified. (Policy expert 2)

I looked at the data one year before death, and there were about 2,000 people. They were long-term care grades 1 and 2, and there were no data on the medical services they used. However, there were death reports from the National Statistical Office. This is a real blind spot. (Policy expert 3)

V. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study conducted two FGIs with seven experts in the field of elderly welfare to explore ways to improve the ability of the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System to identify elderly welfare blind spots. The results of the analysis revealed new potential target ranges and a variety of predictive variables that can be applied to the risk prediction model of the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System.

First, the target of the risk prediction model for elderly welfare blind spots should include not only the gaps in public benefits, but also those whose welfare needs are not met. In other words, the target of elderly welfare blind spot detection should be households with elderly members whose needs are not fully met, regardless of whether they are receiving or using welfare benefits within the system.

According to the results of the FGI, the target of elderly welfare blind spots should include major elderly welfare policy programs, in addition to the current welfare blind spot targets of basic livelihood security, the lower-income bracket, and the basic pension. In particular, it is necessary to prioritize home-visit services. In addition, services for elderly alcoholics and the Elderly Protection Agency can also be targeted.

In order to create a model that takes into account the sufficiency of needs, it is necessary to collect and return welfare need data to the machine, rather than simply the status of receiving or not receiving benefits. The current prediction model only returns the actual status of receiving public benefits, so those who have welfare needs but have never become beneficiaries due to structural limitations of the system, or those who are currently receiving benefits, are excluded from the target group. If the accumulation of feedback on various elderly welfare needs and sufficiency is accumulated and machine learning evolves, the prediction of “the state of elderly who are not fully met with their needs” can be made more accurate.

The characteristics of elderly related to elderly welfare blind spots that were derived through the FGI include age, household structure, mismatch between administrative residence and actual residence, isolation, and information accessibility. These show the characteristics of elderly people who do not know the social security system well or have to give up applying for benefits and services halfway. If the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System reflects these characteristics of elderly people by linking administrative information, it can identify elderly welfare blind spots that can be derived from applicationism.

Specifically, the following administrative information systems can be linked to the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System to extract linked information and apply it to the risk prediction model:

Resident registration database

Social Security Information System (Happyeeum)

Elderly Care Customized System

Vulnerable Elderly Support System

Elderly Employment Business System

Long-Term Care Information System

National Insurance DB

| Operating organization | information system | Link information |

| Ministry of Public Administration and Security | Resident registration computer database | Age, household type, administrative residence, etc. |

| Korea Social Security Information Institute | Happy e-eum | Disability status, type of disability, etc. |

| Korea Senior Human Resources Development Institute | Senior job work system | Information on those who failed to apply for benefits and services, Information on those who stopped using benefits and services, reasons for discontinuation/termination of application for benefits and services, etc. (changes in health, continuous participation, use of similar services, age, etc.) |

| Korea Social Security Information Institute | Vulnerable elderly support system | |

| Elderly customized care system | ||

| National Health Insurance Corporation | Long-term care integrated information system | Information on those who failed to apply for a grade, gender of main applicant, target for family counseling support project, etc. |

| Health Insurance DB | Multi-morbidity code (chronic disease) without medical treatment at a medical institution in the past year |

<Table 5> Linkage information for constructing predictors of blind spot prediction model for elderly welfare

Based on the linked information from the elderly welfare-related systems presented in <Table 5>, if predictive variables reflecting the characteristics of elderly people are applied to the prediction model, the possibility of identifying elderly welfare blind spots that need services despite having welfare needs will increase.

Even if the targets and variables derived from the results of this study are reflected in the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System, the problem is likely to continue unless efforts are made to improve the system and delivery system to solve the elderly welfare blind spot.

First, the need for system improvement can be considered by the example of the caregiver obligation standard. Since January of this year, the caregiver obligation standard for elderly and single-parent beneficiaries of the subsistence allowance has been abolished, which is expected to partially resolve the blind spot of the basic livelihood security system for the elderly (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2021). However, the caregiver obligation standard still exists in medical assistance. Therefore, continuous institutional improvement is needed to resolve the blind spot of medical assistance, which is not met even though there is a welfare need due to the structural limitations of the system (Hwang Dok-kyung, 2020).

Second, efforts to improve the delivery system should also continue. FGI participants suggested that the obstacle to the identification of elderly welfare blind spots is derived from the limitations of bureaucracy, such as the vertical decision-making system, departmental barriers, and complex decision-making stages of the government, which is the implementing entity. Even if institutional improvement is made to respond to the needs of the elderly, if the delivery system is not improved on the premise of mutual cooperation between departments or organizations operating similar programs, the welfare blind spot will not be resolved.

Third, the government also needs to think about whether there are resources available to provide to the elderly who are in the blind spot, rather than how to identify them. In particular, local governments should establish a concrete system to resolve the blind spot of elderly welfare in the region based on information management through public-private cooperation and information linkage for resource management. To this end, local governments should expand the number of dedicated personnel in Eupmyeon-dong and strengthen support for the detection and support of welfare blind spots based on sufficient local resources.

Specifically, the government should:

- Improve the system to ensure that all elderly people who need welfare are eligible for it, regardless of their income or family situation.

- Make the delivery system more efficient and effective by reducing bureaucratic barriers and promoting collaboration between different agencies.

- Invest in local resources to ensure that there are sufficient resources available to support elderly people in need.

By taking these steps, the government can help to ensure that all elderly people in Korea have access to the support they need.

Even if the targets and variables derived from the results of this study are reflected in the Welfare Blind Spot Detection and Management System, the problem is likely to continue unless efforts are made to improve the system and delivery system to solve the elderly welfare blind spot.

First, the need for system improvement can be considered by the example of the caregiver obligation standard. Since January of this year, the caregiver obligation standard for elderly and single-parent beneficiaries of the subsistence allowance has been abolished, which is expected to partially resolve the blind spot of the basic livelihood security system for the elderly (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2021). However, the caregiver obligation standard still exists in medical assistance. Therefore, continuous institutional improvement is needed to resolve the blind spot of medical assistance, which is not met even though there is a welfare need due to the structural limitations of the system (Hwang Dok-kyung, 2020).

Next, efforts to improve the delivery system should also continue. FGI participants suggested that the obstacle to the identification of elderly welfare blind spots is derived from the limitations of bureaucracy, such as the vertical decision-making system, departmental barriers, and complex decision-making stages of the government, which is the implementing entity. Even if institutional improvement is made to respond to the needs of the elderly, if the delivery system is not improved on the premise of mutual cooperation between departments or organizations operating similar programs, the welfare blind spot will not be resolved.

Finally, the government also needs to think about whether there are resources available to provide to the elderly who are in the blind spot, rather than how to identify them. In particular, local governments should establish a concrete system to resolve the blind spot of elderly welfare in the region based on information management through public-private cooperation and information linkage for resource management. To this end, local governments should expand the number of dedicated personnel in Eupmyeon-dong and strengthen support for the detection and support of welfare blind spots based on sufficient local resources.

This study is different from previous studies in that it redefines the concept of elderly welfare blind spots and suggests linked information that can be applied to elderly welfare-specific prediction models in order to overcome the limitations of the existing welfare blind spot detection and management system. However, it is limited in that it does not present a specific prediction model that applies the variables derived from the research results.

The government plans to expand the criteria for crisis households in welfare blind spot detection projects from low-income households to include housing, emotional, and care issues for specific targets such as the elderly and people with disabilities through the introduction of the next-generation social security information system (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2019b). To this end, follow-up studies should develop a specific elderly welfare blind spot detection model that directly applies the concepts of elderly welfare blind spots, the scope of major elderly welfare programs, and predictive variables presented in this study to the next-generation social security information system.

In the future, it is necessary to continue discussions on how to reflect variables that exist in the system linkage among information reflecting the diverse characteristics of the elderly. Follow-up studies are also needed to evaluate the elderly-specific welfare blind spot detection and management system that reflects the needs of elderly welfare.

Lastly, in the process of discovering blind spots in elderly welfare, ethical issues that may arise as a result of linking various administrative data to the welfare blind spot discovery management system should not be overlooked. Even though it is possible to use personal information without the consent of the information subject to discover welfare blind spots under the current law, information subjects, public officials in charge, welfare experts, and policy makers need to know what information is applied to the prediction model, and to identify the prediction model and welfare blind spots. Efforts are needed to disclose and explain information so that the operating principles of the management system can be clearly understood. In fact, in recent years, discussions have been active in Western countries, including the United States, about the legitimacy and effectiveness of using machine learning-based prediction models in the field of child protection. In particular, the importance of transparent information disclosure and establishing governance where policy experts and field experts can participate in decision-making about prediction models is being highlighted (Eun-hee Han, Yun-hee Choi, 2020). Therefore, if the blind spot prediction model specialized for elderly welfare presented in this study is developed and used in the welfare blind spot discovery management system, follow-up research will be conducted to determine the ethical issues and decision-making governance that should be considered when using the elderly welfare blind spot prediction model. Specific alternatives should be discussed.