Management of heart failure in patients with kidney disease—updates from the 2021 ESC guidelines

by Nicola C Edwards, et al.

Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 38, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 1798–1806, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfad011

While clinical trials over almost 40 years have enabled the guidelines to recommend multiple drugs with clear evidence of prognostic benefit in HFrEF, data for HFmrEF and HFpEF phenotypes have been less consistent, a difficulty widely thought to reflect heterogeneity and comorbidities across the patient cohorts as well as differential treatment effects. There are major changes in recommended treatment in the 2021 guidelines which are detailed below. The most important by far is the introduction of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2-I) for patients with HFrEF independent of diabetic status.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

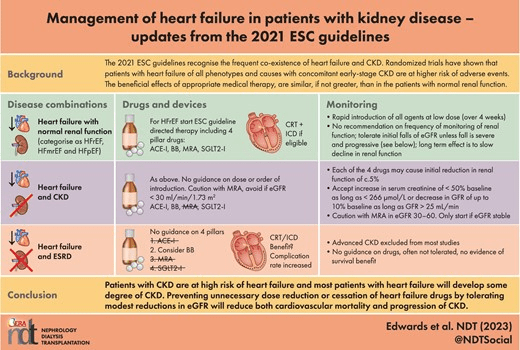

The major strategy change in the 2021 guidelines has been termed the ‘Foundational 4 Pillars’ (Fig. 2). These consist of the three traditional drug classes: (i) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), which are recommended to replace ACE-I in ambulatory persistently symptomatic patients or in stable hospitalized patients who are ACE-I naïve patients, or angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARB) if these are not tolerated; (ii) beta blockers (BB); and (iii) mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA). The fourth pillar is SGLT2-I (currently dapagliflozin or empagliflozin), which receive a new Class I recommendation irrespective of diabetic status. These drugs were introduced to treat hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes by causing glycosuria but have been incorporated into HF guidelines because of findings of impressive reductions in cardiovascular mortality (and in the case of dapagliflozin, total mortality) and in hospitalization for HF (HHF) in large placebo controlled RCTs in patients with HFrEF irrespective of diabetic status and in CKD with eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [13–15]. The new algorithm has moved away from slow sequential introduction and up-titration of drugs and instead focusses on rapid, low-dose introduction of the four ‘pillar’ treatments over 4 weeks. The order in which these therapies are introduced remains debated and in CKD is perhaps more complex because of their effects on renal haemodynamics and on the risk of hyperkalaemia. A proposed strategy for initiation and monitoring according to eGFR has recently been proposed involving careful monitoring and the use of MRA in moderate CKD (eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2) only if eGFR remains stable on ACE-I, BB and SGLT2-I [16].

Figure 2: The ‘Foundational 4 Pillars’. The 2021 ESC guidelines advocates the rapid introduction of all four pharmacological agents at low doses to reduce cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. These agents have also been demonstrated to be effective in CKD and renal outcomes. As HF and CKD often co-exist and exacerbate each other, using these drugs for both conditions should halt progressive decline of both organs in these patients.

The rationale for the change from ESC 2016 ‘traditional recipe’ reflects the prolonged duration (>6 months) of sequential introduction and up-titration if clinicians continue to strive to achieve target doses of each individual drug. This outdated approach has been superseded firstly because consistent data show that a low dose of each of four agents yields significantly greater benefit than that observed with individual dose titration. Secondly, sub-analyses of recent large-scale trials have shown the magnitude of treatment benefit of each pillar drug to be independent of other agents reflecting different mechanisms of action [17]. Thirdly, trial data show that the Kaplan–Meier for curves for the effects of the four pillar drugs on mortality and morbidity begin to separate early, within 30 days [18]. Finally, this approach appears to improve safety and tolerability as evidenced by lower rates of renal dysfunction and lower rates of hyperkalaemia. The 2021 guidelines provide no recommendation on monitoring of kidney function or dose titration if eGFR falls slightly (3–4 mL/min/1.73 m2), as is commonly observed within 2–3 weeks of initiation [19]. In a later section on concomitant HF and CKD, the authors do note that although all the four pillar drugs including SGLT2-I cause an initial reduction in eGFR of around 5%, a moderate early decrease in renal function should not prompt their interruption. They state that an increase in serum creatinine of <50% above baseline, as long as it is <266 μmol/L (3 mg/dL), or a decrease in eGFR of <10% from baseline, as long as eGFR is >25 mL/min/1.73 m2, can be considered as ‘acceptable’. In the longer term, SGLT2-I and the other pillar drugs slow the progressive decline in eGFR, reduce proteinuria and ultimately preserve kidney function compared with placebo and should not be discontinued without strong reason [15, 20].

It is interesting to consider whether a similar approach to the four ‘pillar’ drugs could be applied to the management of CKD patients, especially those with diabetic nephropathy. The established approach of ACE-I/ARB could be combined with rapid prescription of SGLT2-I and MRA. Indeed, trials with both SGLT2-I and the new non-steroidal MRA finerenone mandated treatment with maximally tolerated doses of ACE-I/ARB. There is also strong theoretical and emerging evidence that the combination of SGLT2-I and MRA may have synergistic beneficial effects.

Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction

The HFmrEF (EF 41%–49%) phenotype includes up to 25% of all HF patients and has mortality rates similar to HFrEF [12]. There remains debate as to whether this represents a distinct phenotype or whether it reflects a transition phase depending on response to treatment and variability in the echo assessment of LVEF. To date there are no dedicated trials examining drug treatments in HFmrEF. Current evidence, drawn from observational studies and post hoc analyses of subsets of patients in HFrEF trials, suggests that patients with HFmrEF benefit prognostically from the three older ‘pillar’ drugs leading to weak Class IIa (should be considered, level of evidence C) ESC recommendations. Although SGLT2-I were not recommended in the guidelines, the landmark EMPEROR-Preserved trial in which over 30% of the 5988 patient cohort had an LVEF of 40%–50% demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular death or HHF, primarily driven by lower risk of HHF [21]. Given these impressive clinical outcome benefits and the overlap between HFrEF, HFpEF and HFmrEF, increasing SGLT2-I use is anticipated. In patients with CKD, the presence of HFmrEF should probably be seen as another indication for treatment with an SGLT2-I. This view is supported by the recently published EMPA-KIDNEY trial which confirmed safety and efficacy of empagliflozin across a range of kidney disease severities (eGFR 20–90 mL/min/1.73 m2), levels of proteinuria and presence or absence of diabetes (see ‘Heart failure patients with concomitant CKD’ below) [22].

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFpEF remains the most heterogenous and problematic HF phenotype in terms of definition, aetiology, comorbidities, diagnostic criteria and evidence-based treatment. It accounts for about 50% of HF cases in the community and in patients with CKD [23]. Its prevalence in CKD may be underestimated. Both exercise intolerance and the echocardiographic features of HFpEF including concentric LV remodelling, left atrial dilatation and diastolic dysfunction are common and increase with CKD stage [24]. Abnormalities of both arterial and LV elastance are evident in HFpEF and have been reported in unselected patients with stage 2 and 3 CKD [25]. The guidelines focus on identifying the underlying cause of HFpEF (though they notably fail to mention CKD in this context) to direct appropriate treatment as well as excluding ‘mimics’ such as obesity, physical deconditioning and obstructive sleep apnoea, many of which are common in CKD.

At the time the guidelines were published, no large RCT in HFpEF had achieved a significant reduction in their primary endpoint, although there were very promising signals in sub-group analyses of trials of spironolactone (particularly data from North America) and ARNI [26, 27] and this potentially explains the continued high use of ACE-I, ARNI, BB and MRA by HF physicians. As mentioned above, the EMPEROR-Preserved trial showed that empagliflozin caused a reduction in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death and HHF of 21%, driven primarily by a reduction in HHF. The effect size was comparable to the benefit observed in HFrEF and was consistent across sub-groups of EF [21]. We anticipate that treatment with SGLT2-I will become widely adopted for HFpEF as it has for the other phenotypes. The impressive recent progress made on defining the place of SGLT2-I in HF has made the 2021 guidelines seem already in need of revision and provides support for reconvening guidelines committees to provide an agile and updated response for clinicians as new robust data emerge.